Published: December 15, 2014, 10:42 pm

When they asked the court whether a character condition is an illness of the thoughts from a lawful viewpoint, that was on Wednesday.

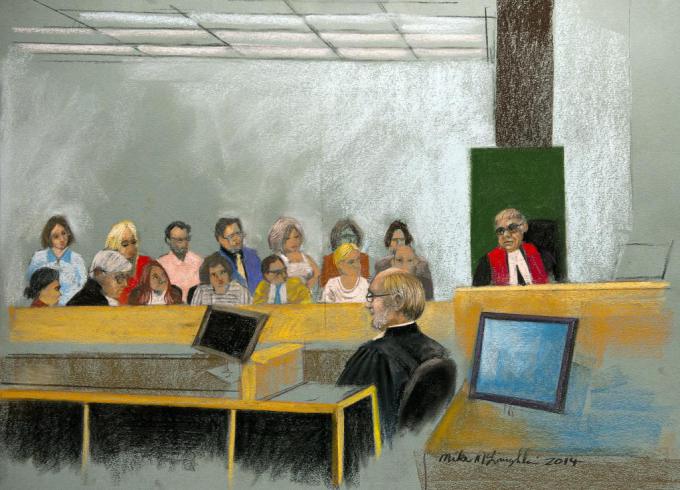

When over the 3 days, the 8 ladies as well as 4 guys started mulling over on Tuesday and also have actually surfaced simply.

But what they didn’t see, either because the prosecution didn’t present it or it was ruled too inflammatory by Quebec Superior Court Justice Guy Cournoyer, was at least as disturbing.

In this category are myriad online posts, made days and in one case more than a month before the homicide, which appear to advertise the horror show that was to come.

The posts were made under a variety of handles, some known to be associated to Magnotta, who at one point had more than 20 Facebook accounts and who certainly knew his way around the web.

But all were made before Lin’s slaying on May 25, 2012.

One, posted on May 15 that year, showed Magnotta in a purple hoodie with what appears to be an ice pick in his hand.

It asks, “There is apparently a video circulating around the deep web and called ‘One Lunatic One Ice Pick Video.’ Does anyone have a copy of it?”

“In advance” is surely the key: Who but Magnotta could have known the name of the grisly video, let alone its details, before it was made (in Montreal, not San Francisco), let alone uploaded to various gore sites?

In fact, the online ads were posted even before Magnotta shot the opening scenes of the dismemberment video, wherein with small electric saw in hand he straddled the sleeping naked body of a still-unidentified young man who was bound at the feet.

Those scenes were shot May 18-19, 2012, about a week before Magnotta killed Lin. They were edited to appear as the beginning of the dismemberment video.

All the jurors heard about the ads — which are completely in keeping with what they have learned about Magnotta’s unquenchable need for attention and his strategic way of manufacturing online buzz — came last month.

In Python Christmas, Magnotta at one point carries the kitten in a Santa hat, then dons it himself as he plays with Jasmine on a bed.

Since Magnotta is pleading not guilty by dint of mental disorder, his state of mind and his ability to appreciate what he was doing and to know right from wrong is the critical issue for the jurors.

Through his lawyer Luc Leclair, the 32-year-old Toronto native on the first day of trial admitted the “physical part” of all the charges he faces. But he is claiming his alleged major mental illness means he shouldn’t be held criminally responsible.

The other significant video the jurors didn’t see is a 20-minute audition Magnotta did in Toronto on Feb. 13, 2008, for a plastic surgery reality TV show called Plastic Makes Perfect 2.

In it, he presented himself as a model in adult films and Internet shows, exaggerated the amount of surgical work he’d had and said he now wanted implants for his chest and arms. When asked how important his looks were, he replied, “OMG, that’s No. 1!”

Throughout, he was confident, articulate and clearly pleased with himself.

Cournoyer ruled the tryout video was a possible “game-changer,” relevant and admissible, but far too prejudicial for the jurors to view.

Its significance, as with the cat videos, was that Magnotta seemed so self-possessed, so organized and so decidedly not delusional — all at a time when he was purportedly under care for his alleged schizophrenia.

Similarly did Magnotta’s conduct vary during the 11-week-long trial itself.

Before the jurors, he was quiet and meek, bent over so far it was often difficult even to see him in the cavernous prisoner’s box. With seats for 20, divided into three compartments, the box was designed for gang trials.

But when the jurors weren’t there — and given the number of objections and snits from his lawyer, Leclair, they were out of court more than they were in it — Magnotta was far more animated.

The second the last of the jurors left the room, he would pop up, like a groundhog.

He chatted with the security guard who brought him to court, or shuffled, his legs in shackles, to the phone in the box so he could talk to Leclair.

As for Leclair, as he inimitably told Cournoyer once late last month, “You said you’ve never seen a lawyer like me.”

Few others had either.

Leclair, a bilingual lawyer who is based in Toronto, was regularly late arriving at court; often couldn’t or wouldn’t say why he was objecting to something, and was openly defiant with the judge, once telling him, “If Your Honour is going to take that attitude I’m going to stop right now and demand a mistrial.”

Another time, Leclair complained that “to do this case with the budget I’ve been given is ridiculous” and suggested the judge had “never done a murder trial on legal aid.”

In October, Leclair had a utter meltdown — Cournoyer had denied one of his objections and Leclair snapped, “I need a break,” then complained “I can’t stand here being cross-examined,” said “I don’t feel well,” and finally demanded time “So I can go for a walk.”

The judge said he understood “what an exacting and demanding a retainer” Leclair had, but said, “That’s what a trial is all about.”

Leclair was so unresponsive about what was wrong that Cournoyer asked gingerly if he had doubts about his ability to continue, while others in the room wondered if he was having a seizure.

Originally estimated to last between six and eight weeks, the trial dragged on for three more; its pace was leisurely. Yet, according to Leclair, it moved so quickly he said he felt like he was on the Train à Grand Vitesse between Paris and Lyon.

“There’s never a pause,” he said.

But perhaps his most egregious comment came when, the day after the jurors had seen the ghastly dismemberment video, Leclair asked for an extra day off, claiming that the viewing was “extremely difficult for Mr. Magnotta.”

This article is courtesy of Christie Blatchford – ocanada

Related articles across the web